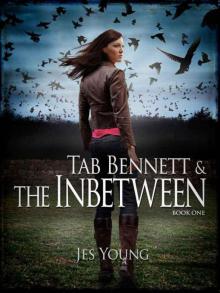

Tab Bennett and the Inbetween Read online

Tab Bennett

The Inbetween

By Jes Young

Text Copyright © 2012

All rights reserved

To Cassy

always my first reader and most dedicated fan

Chapter One

While my sister Rivers was dying, I was planting crocus bulbs in my front yard.

While she was fighting for life I was thinking about how pretty the purple and yellow flowers would look poking up through the snow when the spring came. While she was gasping for air I was singing along with the radio to some stupid top 40 song I’d be embarrassed to admit I know. I was tired and achy. I saw the dirt under my nails and then I knew. There was dirt under her nails too.

I could see her struggling in a small dark place. I could feel her panic as the air ran out. Her fingernails snagged and broke on rocks and roots as she clawed at the soil settling above her. The earth closed in all around until there was no light and no air and no sound. There was nothing but the quiet airy emptiness you hear inside a seashell.

Rivers was gone and I was kneeling in the cold, wet grass with a pounding headache and a bloody knee. The vision ended almost as abruptly as it had begun.

Some black birds lifted from their roost in the trees just as Francis came running from the other side of the house.

“What? Are you hurt?” he yelled as he ran toward me. “Are you hurt?”

I struggled to my feet, took one lurching step, and passed out before my head hit the dirt.

********

It was dark and quiet when I woke up.

I didn’t have to lift my head or open my eyes to know where I was. I recognized the lumps in the cushions and the smell of the afghan draped over me. I heard the comforting rumble of men’s voices in a nearby room and knew that I was home, safe and cared for on the couch in the downstairs sitting room at Witchwood Manor. The tapping of a size twelve work boot against the floor told me that my fiancé Robbin was there waiting for me to wake up, watching over me until I did. For the first time ever I found his restless, relentless tap, tap, tapping comforting. It told my heart what to do. Beat, beat, beat, it said. It reminded my lungs to fill and empty and fill again. Turns out those things aren’t entirely involuntary.

He was the first thing I saw when I opened my eyes. He was leaning against the doorframe, still in his work clothes, looking angry and sad and, of course, beautiful. He just couldn’t help that – even when tragedy really called for him to be less sensational looking. He was tall and muscular with a strong chin and a soft, sweet mouth. His eyes were the color of the ocean on a sunny day and his short hair was a sandy blond. I sighed, wishing I were waking up with him under happier circumstances.

“Hey,” I said.

He crossed the room to the couch in a few strides and stood looking down at me. “You OK?”

My head hurt, my knee ached, and a vision of my sister suffocating to death was playing on a constant loop inside my head. ‘OK’ was not a word that leapt immediately to mind. I nodded anyway, pretending I was.

“Did they find her yet?” I asked.

He shook his head. “Francis and Matt are searching the woods but I don’t think they’re gonna find anything. There’s no moon tonight.”

The practical upshot of that information, as it pertains to my story, is if you’re looking for a place to dig a shallow grave into which you can drop the body of a badly beaten but still living young woman, my grandfather’s house, Witchwood Manor, is the spot for you. On a moonless night, the sky is pitch black and the many acres of woods and gardens and fields that surround the old stone mansion are the darkest kind of dark. With no moon and no light and no shadows, it’ll just be you, your murderous intentions, and a shovel. I can almost guarantee you won’t get caught because for three months in a row someone used that complete cover of darkness to bury my sisters alive. And none of us saw a thing.

When I looked up Robbin was eyeing me cautiously, probably waiting for me to cry or scream the way I did when Molly and Becky disappeared. I was waiting for the tears too, but they didn’t come. My eyes burned, but they were dry.

“I’m OK, Robbin. Really I am.” I sat up just to prove that I could, ignoring the dizzy, whirling feeling in my head.

“Bennett thinks I should take you to the emergency room. Maybe he’s right. Maybe we should drive over to St Luke’s, let the docs look you over. Just to be sure.”

“I don’t want to go to the hospital.”

I knew he was trying to decide whose wrath he’d rather contend with – mine or my grandfather’s – when he sat down beside me. I rested my head against his shoulder and he began to run his fingers through my long, dark hair. I honestly don’t know if he was soothing me or checking for head injuries.

“We don’t have to go to the hospital,” he whispered. “I’ll take you anywhere you want to go. We could just leave right now.”

I can’t tell you how many times I’ve looked back on that moment, wondering what would have happened if I’d let him take me away that night. Where would I be right now? Who would I be? So much pain could have been avoided. So many things would never have happened. But I missed the look of hope in his eyes and I didn’t realize what was being offered.

“I think I should stay.”

“Whatever you say, tough guy.” He smiled, but it was his sad smile instead of the real one.

“Should I get Bennett then? He and George are in the study waiting for you to wake up.”

Before all this started, Pop and I were close. But over the days and weeks since my sister Molly disappeared our relationship had twisted into a sort of complicated, adversarial thing that consisted mostly of a delicate combination of half-truths, lies, and strained silences.

“He can wait.”

Rivers can wait too.

I knew that for sure because I’d just watched her die in a vision so vivid it gave Technicolor a run for its money. I had struggled along with her while she was pulled into the ground, while the dirt covered her eyes and mouth. I could still taste the rich, dark soil she pulled into her lungs with every gasping breath. Now I was safe and warm in the house we’d both been raised in and she was buried just a foot or two below the surface of the earth somewhere on its grounds.

********

Pop and I sat across from each other in his dimly lit study. He held my hand, palm up, pressed between the two of his. I felt calm and light and strangely far away. I looked up and saw stars where the ceiling should’ve been. I could see the Milky Way. I could count the loops in Orion’s belt.

“Do you know where Rivers is?” he asked in a quiet, almost sing-song voice that called my attention back to him. “Where is your sister, Tabitha?” Colors began to swirl in his eyes, the blue darkened until the iris was such a deep navy I could barely see the pupil.

“I don’t know,” I said. I was having trouble thinking straight. My mind felt cloudy. My body felt like it would float away if not for the magnetic pull of my grandfather’s eyes. The color shifted to the barely-blue of the sky on a cloudy morning. I stared at him, unable to look away, as the color of his eyes drifted from gray to blue to black. I didn’t answer him or blink or move. I watched the colors, lost in the tempest.

“Are you sure you don’t see her? Look harder.” His eyes became the color of ripe blueberries.

“No.”

Once again the color drained from his eyes, leaving them a misty, washed out gray. “I think you do see her,” Pop whispered. “Be brave. Only you can see her where she lies.” His eyes darkened to nighttime sky. I watched the stars twinkle and burn there, mirroring those on the ceiling. “Tell me what you see.”

I answered without thinking, without knowin

g what I would say. The voice was mine but the words were not. “I see betrayal and blood and deepest darkness. I see light and magic and sex.”

Pop’s eyes went lavender – the same strange shade as mine – and he dropped my hand like it had burned him. The clouds in my head cleared instantly. “I want to stop now.” I said, stepping away.

He shot to his feet. “We will stop after you have told me what you see.” He grabbed for my hand again but I pulled it back. My cousin George, who I’d honestly forgotten was even in the room, subtly moved between us.

“I don’t see anything.”

“Why are you lying to me?”

“How can you accuse me of lying? We all know I’m not the member of this family who is pathologically incapable of telling the truth.”

George actually gasped.

“Meaning?” Pop’s narrowed eyes were their regular cloudless blue.

“Meaning that you have done nothing but lie to me and everyone else since the night Molly disappeared. Meaning that Becky and Rivers might still be alive if you’d told the truth from the beginning. Meaning that I don’t trust you at all anymore.”

Pop looked furious for a split second before he straightened his tie and smoothed his hand over his silver hair. “Since this conversation is pointless, I am going outdoors to find the others. Perhaps I can be of some help in the search.”

“I doubt it – unless they need someone to stand around barking out commands.”

I was shaking as he left, shocked at myself for yelling at him, which was something I never did. When I looked at George, I could tell he was shocked too.

“Well that was unexpected,” he said.

“More like overdue,” I replied, sounding braver than I felt.

Rivers’ death brought the whole thing to a head, but the rift between Pop and me had been growing wider every day since I woke from my first vision – completely hysterical – on the night Molly disappeared.

When I’d calmed down, he explained to me in his quiet, calm way about “families like ours” and “the need for privacy during times like these.” I didn’t know what he meant but I listened and nodded, watching the colors that swirled and sparkled in his eyes. By the time the conversation was over, I’d somehow agreed that it was wise not to call the police, that we could best take care of the situation on our own.

A few days later Francis found Molly’s body buried just on the edge of the ring of woods that surround Witchwood Manor. Pop had her cremated privately and simply told anyone who asked that she was traveling in Europe on an open-ended ticket. She was studying the great masters in Italy. She was thinking of enrolling in a program at the Cordon Bleu. We didn’t know when she’d be back. He always worked in some comment about how she was off finding herself. I guess he thought it made her sound young and silly and impetuous – instead of dead.

But if one vanishing granddaughter is easy to explain, two starts to look a little suspicious. A month later, when Becky disappeared, he didn’t have a choice – he called the police to file a missing persons report. While we waited for them to come out to the house, Pop held my hands and explained it all to me in the same soft voice, with the same kaleidoscoping eyes. It was better, best, to let him handle the situation his way. He would tell the police a story that would explain Becky’s disappearance without drawing suspicion and we would look for the truth ourselves.

I know what you’re thinking; if someone suggests lying to the police while members of his family are being kidnapped and murdered, it’s probably because he is a kidnapper and a murderer. But that didn’t even cross my mind. I was too busy looking up at the stars blinking and shining on the ceiling of the study.

By the time the police arrived I’d memorized Pop’s story about Becky’s violent boyfriend, the fights they’d had, the threats he’d made. I told the officer who took my statement how scared I was of him, how frightened I’d been for my sister’s safety. After talking to each of us, discretely of course, we were Bennetts after all and that means something in a town called Bennett Falls, the police concluded that Becky had most likely run off with her boyfriend. As she was an adult, there was nothing we could do about it – even if we disapproved. Case closed.

“He’s afraid he’s going to lose you.” George’s voice pulled me out of my head and back into the moment.

I laughed. Not to be a jerk or anything, but because I thought that was a genuinely funny thing to say. “Considering the circumstances, I’d say that’s a reasonable fear.”

It was pretty clear to me that someone wanted the Bennett girls dead, that he was working his way down a list with our names on it, that mine was the only one still without a check mark next to it.

George frowned. “Don’t be like that.”

“I’m not being like anything.”

“You are. You’re being cold and distant and a little bit bitchy.” He came and sat on the edge of Pop’s desk.

“I’m so sorry if my fear of death is inconveniencing you.”

He laughed, replacing his smile with an alarmingly serious expression once it became clear that I wasn’t going to join in. “You trust me, don’t you?”

“No,” I said. But that was a lie. If I trusted anyone, it was George.

“Do you trust me?” he asked again.

I nodded, but grudgingly.

“Then believe me when I say that I won’t let anyone hurt you.”

I had the good manners not to ask if he had made the same promise to my sisters.

*******

Only thirteen months older than me, Rivers was my constant companion growing up. And although we had nothing in common; she was shy and I’m a social butterfly; she was a reader and I’m a runner; she was a thinker and I tend to let my heart carry me away, she was also my best friend. We went everywhere together and told each other everything. Well, I told her everything anyway. Rivers kept some secrets from me.

She ran away the summer before we graduated high school without so much as a word. Not even a note. I didn’t hear from her until two years ago when she showed up back home, tired and sad and looking like she’d done more than her share of rambling.

She’d probably still be alive if she’d just stayed away.

I pushed the thought out of my mind. If I wasn’t very careful, the vision of her death would start up again in my head and I knew from previous experience that once it started, it would be hard to stop.

Look, I’m not the sort of person who looks for a bright side to every situation – sometimes even the silver lining is black – but if I was, I’d point to that, to previous experience, as the one good thing to come with each vision. I won’t say I was getting used to them because I don’t think it’s possible to get used to something so horrific, but I was learning how to separate myself from them, how to keep them from creeping back into my head once they’d passed.

The first time it happened I was completely unprepared. I was in the kitchen making a peanut butter and banana sandwich when I started to feel lightheaded. I steadied myself against the counter, closing my eyes so the room would stop spinning. When I opened them I was with Molly, I was Molly, and I was in the dark gasping for air. I panicked until there was nothing left to breathe and then she died and I passed out, hitting my head on the edge of the counter as I fell. I woke up hours later, hysterical and terrified and convinced I was dead.

The next month, I relived the whole series of events, from the vision to the crash of my head against the ground to the moonless night to the shallow grave somewhere close enough to Witchwood Manor that anyone one of us, leaning out the window at the right time, might have seen someone dragging Becky’s body across the lawn. I handled it better. A little better anyway. I mean, at least I knew I wasn’t dead.

“They’re back,” George said a moment before I heard the kitchen door open and the sound of voices in the hall. As they got closer, I heard Matthew mumbling something and Francis whisper yell a response. George smiled nervously and shook his head, ind

icating that it was nothing to worry about.

Robbin came into the study first, followed by Francis and Matthew who were staring murder at each other. They were all filthy; dirt caked on their hands and smeared across their faces. Matthew had leaves in his long blond hair and a few broken bits of twig sticking out of his braid. Pop walked in a moment later without so much as speck of dirt on him. He had obviously been a huge help.

Taking a seat behind his desk, he reached for the telephone. When we didn’t get the hint, he held the receiver away from his mouth to say, “You should all go to bed. We have done all we can for tonight.”

“We could call the police,” I said. I turned to my cousins and fiancé for someone to back me up me but none of them would even look at me.

Tab Bennett and the Inbetween

Tab Bennett and the Inbetween